Vo Nguyen Giap, the relentless and charismatic North Vietnamese general whose campaigns drove both France and the United States out of Vietnam, died on Friday in Hanoi. He was believed to be 102.

The death was reported by several Vietnamese news organizations, including the respected Tuoi Tre Online, which said he had died in an army hospital.

General Giap was among the last survivors of a generation of Communist revolutionaries who in the decades after World War II freed Vietnam of colonial rule and fought a superpower to a stalemate. In his later years, he was a living reminder of a war that was mostly old history to the Vietnamese, many of whom were born after it had ended.

But he had not faded away. He was regarded as an elder statesman whose hard-line views had softened with the cessation of the war that unified Vietnam. He supported economic reform and closer relations with the United States while publicly warning of the spread of Chinese influence and the environmental costs of industrialization.

To his American adversaries, however, from the early 1960s to the mid-1970s, he was perhaps second only to his mentor, Ho Chi Minh, as the face of a tenacious, implacable enemy. And to historians, his willingness to sustain staggering losses against superior American firepower was a large reason the war dragged on as long as it did, costing more than 2.5 million lives — 58,000 of them American — sapping the United States Treasury and Washington’s political will to fight, and bitterly dividing the country in an argument about America’s role in the world that still echoes today.

A teacher and journalist with no formal military training, Vo Nguyen Giap (pronounced vo nwin ZHAP) joined a ragtag Communist insurgency in the 1940s and built it into a highly disciplined force that ended an empire and united a nation.

He was charming and volatile, an erudite military historian and an intense nationalist who used his personal magnetism to motivate his troops and fire their devotion to their country. His admirers put him in the company of MacArthur, Rommel and other great military leaders of the 20th century.

But his critics said that his victories had been rooted in a profligate disregard for the lives of his soldiers. Gen. William C. Westmoreland, who commanded American forces in Vietnam from 1964 until 1968, said, “Any American commander who took the same vast losses as General Giap would not have lasted three weeks.”

General Giap understood something that his adversaries did not, however. Early on, he learned that the loyalty of Vietnam’s peasants was more crucial than controlling the land on which they lived. Like Ho Chi Minh, he believed devoutly that the Vietnamese would be willing to bear any burden to free their land from foreign armies.

He knew something else as well, and profited from it: that waging war in the television age depended as much on propaganda as it did on success in the field.

These lessons were driven home in the Tet offensive of 1968, when North Vietnamese regulars and Vietcong guerrillas attacked scores of military targets and provincial capitals throughout South Vietnam, only to be thrown back with staggering losses. General Giap had expected the offensive to set off uprisings and show the Vietnamese that the Americans were vulnerable.

Militarily, it was a failure. But the offensive came as opposition to the war was growing in the United States, and the televised savagery of the fighting fueled another wave of protests. President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had been contemplating retirement months before Tet, decided not to seek re-election, and with the election of Richard M. Nixon in November, the long withdrawal of American forces began.

General Giap had studied the military teachings of Mao Zedong, who wrote that political indoctrination, terrorism and sustained guerrilla warfare were prerequisites for a successful revolution. Using this strategy, General Giap defeated the French Army’s elite and its Foreign Legion at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, forcing France from Indochina and earning the grudging admiration of the French.

“He learned from his mistakes and did not repeat them,” Gen. Marcel Bigeard, who as a young colonel of French paratroops surrendered at Dien Bien Phu, told Peter G. Macdonald, one of General Giap’s biographers. But “to Giap,” he said, “a man’s life was nothing.”

Hanoi’s casualty estimates are unreliable, so the cost of General Giap’s victories will probably never be known. About 94,000 French troops died in the war to keep Vietnam, and the struggle for independence killed, by conservative estimates, about 300,000 Vietnamese fighters. In the American war, about 2.5 million North and South Vietnamese died out of a total population of 32 million. America lost about 58,000 service members.

“Every minute, hundreds of thousands of people die on this earth,” General Giap is said to have remarked after the war with France. “The life or death of a hundred, a thousand, tens of thousands of human beings, even our compatriots, means little.”

A Student of Revolution

Vo Nguyen Giap was born on Aug. 25, 1911 (some sources say 1912), in the village of An Xa in Quang Binh Province, the southernmost part of what would later be North Vietnam. His father, Vo Quang Nghiem, was an educated farmer and a fervent nationalist who, like his father before him, encouraged his children to resist the French.

Mr. Giap earned a degree in law and political economics in 1937 and then taught history at the Thanh Long School, a private institution for privileged Vietnamese in Hanoi, where he was known for the intensity of his lectures on the French Revolution. He also studied Lenin and Marx and was particularly impressed by Mao’s theories on combining political and military strategy to win a revolution.

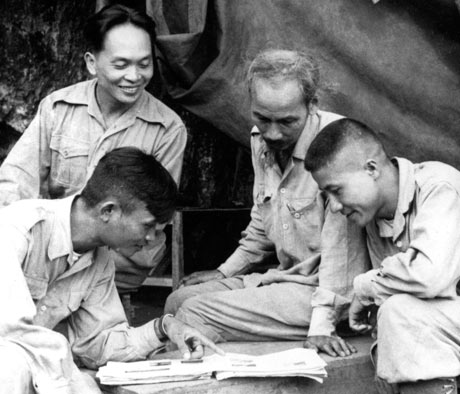

In 1941, Ho Chi Minh, the founder of the Vietnamese Communist Party, chose Mr. Giap to lead the Viet Minh, the military wing of the Vietnam Independence League.

In late 1953, the French established a stronghold in the northwest at Dien Bien Phu, near the border with Laos, garrisoned by 13,000 Vietnamese and North African colonial troops as well as the French Army’s top troops and its elite Foreign Legion.

After an eight-week siege by Communist forces, the last French outposts were overrun on May 7, 1954. The timing was a political masterstroke, coming on the very day that negotiators met in Geneva to discuss a settlement. Faced with the failure of their strategy, French negotiators gave up and agreed to withdraw. The country split into a Communist-ruled north and a non-Communist south.

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, President Dwight D. Eisenhower and later President John F. Kennedy looked on with rising anxiety as Communist forces stepped up their guerrilla war. By the time Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in 1963, the United States had more than 16,000 troops in South Vietnam.

General Westmoreland relied on superior weaponry to wage a war of attrition, in which he measured success by the number of enemy dead. Though the Communists lost in any comparative “body count” of casualties, General Giap was quick to see that the indiscriminate bombing and massed firepower of the Americans caused heavy civilian casualties and alienated many Vietnamese from the government the Americans supported.

With the war in stalemate and Americans becoming less tolerant of accepting casualties, General Giap told a European interviewer, South Vietnam “is for the Americans a bottomless pit.”

A Turning Point

On Jan. 30, 1968, during a cease-fire in honor of the Vietnamese New Year (called Tet Nguyen Dan), more than 80,000 North Vietnamese and Vietcong troops hit military bases and cities throughout South Vietnam in what would be called the Tet offensive. For the Communists, things went wrong from the start. Some Vietcong units attacked prematurely, without the backing of regular troops as planned. Suicide squads, like one that penetrated the United States Embassy in Saigon, were quickly wiped out.

Despite some successes — the North Vietnamese entered the city of Hue and held it for three weeks — the offensive was a military disaster. The hoped-for uprisings never took place, and some 40,000 Communist fighters were killed or wounded. The Vietcong never regained the strength it had before Tet.

But the fierceness of the assault illustrated Hanoi’s determination to win and shook the American public and leadership.

“The Tet offensive had been directed primarily at the people of South Vietnam,” General Giap said later, “but as it turned out, it affected the people of the United States more. Until Tet, they thought they could win the war, but now they knew that they could not.”

He told the journalist Stanley Karnow in 1990, “We wanted to show the Americans that we were not exhausted, that we could attack their arsenals, communications, elite units, even their headquarters, the brains behind the war.”

He added, “We wanted to project the war into the homes of America’s families, because we knew that most of them had nothing against us.”

The United States government began peace talks in Paris in May 1968. The next year, Nixon began withdrawing American troops under his policy of Vietnamization, which called for the South Vietnamese troops to bear the brunt of the fighting.

In March 1972, the North Vietnamese carried out the Easter offensive on three fronts, expanding their holdings in Cambodia and Laos and bringing temporary gains in South Vietnam. But it ended in defeat, and General Giap again bore the brunt of criticism for the heavy losses. In summer 1972, he was replaced by Gen. Van Tien Dung, possibly because he had fallen from favor but possibly because, as was rumored, he had Hodgkin’s disease.

Although he was removed from direct command in 1973, General Giap remained minister of defense, overseeing North Vietnam’s final victory over South Vietnam and the United States when Saigon, the South’s capital, fell on April 30, 1975. He also guided the invasion of Cambodia in January 1979, which ousted the brutal Communist Khmer Rouge. The next month, after Hanoi had established a new government in Phnom Penh, Chinese troops attacked along the North Vietnamese border to drive home the point that China remained the paramount regional power.

It was General Giap’s last military campaign. He was removed as minister of defense in 1980 after his chief rivals, Le Duan and Le Duc Tho, eased him out of the Politburo. Too prominent to be openly denounced, he was instead made vice prime minister for science and education.

But his days of real power were gone. In August 1991, he was ousted after Vo Van Kiet, a Western-style reformer, came to power.

In his final years, General Giap was an avuncular host to foreign visitors to his villa in Hanoi, where he read extensively in Western literature, enjoyed Beethoven and Liszt and became a convert to pursuing socialism through free-market reforms.

“In the past, our greatest challenge was the invasion of our nation by foreigners,” he told an interviewer. “Now that Vietnam is independent and united, we can address our biggest challenge. That challenge is poverty and economic backwardness.”

Addressing that challenge had long been deferred, he told the journalist Neil Sheehan in 1989. “Our country is like an ill person who has suffered for a long time,” he said. “The countries around us made a lot of progress. We were at war.”