Acrobat, maverick, firecracker. Manchester City's brilliant Italian striker can't help drawing attention to himself

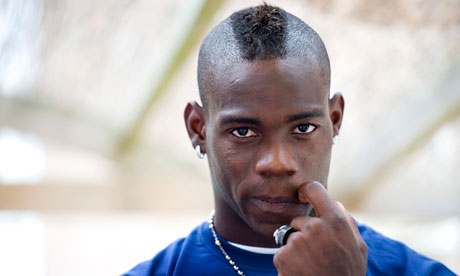

Mario Balotelli, Manchester City's flamboyant Italian striker, is the Premiership's most talked about player. Photograph: Tom Jenkins

Last Saturday it was reported that Manchester City footballer Mario Balotelli had set his house alight with fireworks. On Sunday, he celebrated the first of his two goals in the 6-1 thrashing of Manchester United by lifting his shirt to reveal a vest that said 'Why always me?'

By Tuesday, there were photographs in newspapers showing he had become Manchester's ambassador for firework safety. Solemn and unsmiling, he held a poster of rockets exploding into the sky accompanied by the message: "How safe are you this Bonfire Night?"

He also used the opportunity to reveal that it was friends who set his towels on fire in his bathroom, not him, and that they had been suitably admonished. Just another week in the life of the Premier League's most talked-about footballer.

The fact that Manchester's fire service had no idea that the Italian striker was the new face of the campaign just adds spice to the story.

"It was Manchester City that organised the photoshoot. We didn't know about it until we saw the photograph," a spokeswoman for Greater Manchester fire and rescue service said, adding: "We fully support what they are doing with regards to Balotelli and fire safety."

A triumph of PR, branding, opportunism and Balotelli chutzpah.

Apart from the goals and fireworks, it's been a quiet few days for the 21-year-old – yes, he was photographed flicking through the porn mag Fiesta in his local newsagents while out shopping with girlfriend Raffaella Fico, and he was transformed into the superhero of a Taiwanese animated cartoon film, and he announced, yet again, that he hoped to become the best player in the world, but that's about it.

In a world of identikit footballers it's not surprising that Balotelli has become such a cult figure. On the pitch he has amazing strength and grace – he strokes balls into the net rather than wallops them, and performs overhead acrobatics in the penalty area – and he frequently infuriates by attempting the impossible or spurning easy chances.

He was substituted in a pre-season friendly after decling an easy chance in front of goal, instead pirouetting, backheeling the ball, and missing. His manager Roberto Mancini said it showed contempt for the fans, the game and the opposition. In recent weeks he has flourished, with six goals in five games.

But it is off the pitch that he has continued to attract most attention. It's not just simply the ever-changing haircuts (Gold stardust number 1, tyre-track mohawk, multicoloured patchwork reminiscent of Matisse's Snail, M shaved into his neck), nor the fireworks.

It's the sports cars he's written off, the unauthorised visits to women's prisons to see what they are like, the cash gifted to homeless people outside casinos at 2am, the fights with teammates on training grounds, the fight with his bib when he couldn't put it on, the £5,000 in cash found in his backpocket when stopped by the police ("Why are you carrying so much money, sir?" "Because I am rich"), the possibly apocryphal story of taking a truant back to school to meet his bullies, the almost certainly apocryphal story that he is allergic to grass.

And on it goes. It's impossible to separate truth from urban myths, and City fans don't care to – preferring to collate all his deeds and misdeeds into a multi-versed tribute that is possibly the longest song in football history, and being extended by the week.

Balotelli was born Mario Burwuah in Palermo, Sicily, to Ghanaian immigrant parents. As a young boy he suffered a life-threatening intestinal illness. The family moved to the wealthy industrial city of Brescia to give his father the opportunity of work in factories. But they had three other children and their living conditions were cramped, and after Mario's operation they asked social services for help.

He was fostered shortly before his third birthday, initially for a year, to Francesco and Silvio Balotelli, a middle-class white couple who already had two sons and a daughter.

Balotelli has stayed with them ever since and calls them his parents, though they never officially adopted him. He claims his parents dumped him and only wanted to know him when he became famous; they say they always wanted him back.

He is particularly close to his adoptive sister Cristina, a journalist who covered the war in Afghanistan and has done much to protect him, and he now appears to have a good relationship with his biological siblings who were not fostered. Cristina Balotelli says he is a complex character.

"Mario is shy, but at the same time he likes to be the centre of attention. He has a strong personality. He knows what he wants; has no fear of anything. He has this ability to be cold – to not feel tension."

As a young boy, he revealed an astonishing gift for football, only equalled by his ability to attract trouble.

He was kicked out of a youth team for disruptive behaviour when he was just seven, and also had to be disciplined after mooning out of the back of a team bus at a jeep full of Italian soldiers.

By his early teens he had the build of a man, and the attitude to go with it.

It's impossible to understand Balotelli without taking race and Italy into account. When he turned professional, black Italian footballers were a rarity – akin to being a black footballer in England in the 1970s or 80s. Bananas were thrown, unforgivable comments made.

The booing of Balotelli started well before he played in Italy's premier league, Serie A, said Ezio Chinelli, chairman of lower league side Lumezzane, where Balotelli was a youth player from nine to 16. "He was drafted in for his debut with the first team at 15 when we were a player short against Padoa.

"He came on for the last 20 minutes and immediately dummied a defender, who flattened him, just as the crowd started chanting abuse Now there is a black kid on every team round here, but 10 years ago he was the first."

Balotelli could not be picked for the national youth team because Italian law prevents the offspring of immigrants obtaining citizenship until they are 18, but he is now a full Italian international.

According to Balotelli's unofficial biographer, Raffaele Panizza, the black child with the thick Brescia accent was acutely aware of the colour of his skin. "He would ask his teacher 'Is my heart red like the others?'", he said.

Throughout his career in Italy, he was the target of racists. The abuse he was subjected to by Juventus fans led to a partial closure of Turin's Olympic stadium. Even outside Inter Milan's San Siro stadium graffiti was daubed: "Non sei un vero Italiano, sei un Africano nero", translating as "You are not a true Italian, you are a black African."

From the start, he was known for his stubborness. He looked sulky, and asked why he should smile when he scored as it was his job. "He rarely celebrated scoring goals back then, just as he doesn't now, and he told me 'I'll celebrate when I score in the Champions' League final'," said Michele Cavalli, a trainer at Lumezzane. Balotelli thought he was the best, and did not take kindly to those who suggested otherwise. "I had him on the bench in a game when he was 13, something he never liked," Cavalli said. "I sent him on when we were 1-0 down, he took on the whole defence and scored, only to then do the same thing again but this time screw the ball wide. We drew 1-1 and I was convinced he missed to punish me, but when I asked him he just smiled."

After an unsuccessful trial with Barcelona at 15, he signed for Inter the following year, scoring two goals on his full debut when he was 17.

But, of course, controversy was to follow. He frequently fell out with players and coaches, was criticised for his attitude to training, and appeared on a satirical television show wearing the top of Inter's great rivals AC Milan.

Not even Jose Mourinho, the self-proclaimed Special One, could control him, calling him "unmanageable".

By the age of 19 he had been transferred to Manchester City for £24m, and reunited with his first manager at Inter, Roberto Mancini. Again, he scored on his debut, and again, controversy followed controversy. It looked as if he wouldn't last the season, especially when he announced he wanted to be back in Italy on his arrival. Mancini has had to constantly berate him. After he was sent off against Dynamo Kiev last season, Balotelli said: "Mancini killed me. He said, 'You're an idiot. I don't know why I bought you!'"

Yet Mancini has also shown him love and respect, and this week said he was one of the best five players in the world. Balotelli calls Mancini a father figure, and even ran over to him and jumped into his arms after scoring an important goal against Everton.

It's early days. He's still only played 35 games for City (scoring 16 goals) but the British public seems to have taken to him because of, not in spite of, his challenging personality.

He is already being compared to Eric Cantona and Paul Gascoigne, both of them troubled mavericks and footballing geniuses. He can play the prankster like Gazza and poet like Cantona (there was something rather beautiful about the ambiguous "Why always me?" T-shirt).

Does Gascoigne see anything of himself in Balotelli? "I think I've done a lot more than set off fireworks in a bathroom. He's got a long way to go to get to my standards."

Has he any advice for him? "I like his style, but he should ease up on the arrogance a bit, especially when he scores. He should show a bit more love towards his own fans. They pay his wages."

But Manchester City fan Noel Gallagher says he doesn't want to see Balotelli maturing too much. "Football needs players like him because most footballers are basically squares. He's a total rock'n'roller. There's a bit of Mario in all of us – well, maybe not Gary Neville – but the rest of us most definitely." In what way? "Have you never wondered what it would be like to set off rockets in your house? Visit a women's prison just for a nosy? Write off a supercar? Deal only in cash? Befriend the mafia? Mario lives life on the edge, so people like you don't have to."

Style watch: Mario Balotelli

The art of the footballer's haircut is long established. But finally, after years of David Beckham's dominance, the discipline has a new hair icon. Mario Balotelli's scalp is the gift that keeps on giving, whether it be a classic skinhead, a bleach-job or a shark-fin mohawk – which is by now surely established enough to earn the status as the modern footballer's mullet. He has also sported what can only be described as the tonsorial expression of a tyre skidmark on his scalp, complete with matching eyebrows and the sort of diamond earrings that only a £120,000-a-week pay cheque can buy.Balotelli's most extravagant cut – a multicoloured paint job resplendent with the No 17 – mirrors his unpredictable persona. Why not No 45 – his shirt number? But perhaps his finest fashion moment came when he wore a giant knitted glove hat as he arrived at the ground. No matter that he doesn't smile after scoring, this piece of woollen eccentricity spoke volumes.

It hasn't always been skilful wardrobe selections from Balotelli. Back in March, the striker betrayed a styling deficiency when he struggled to put on a black and white bib in a pre-match warm up and had to call on the services of a club official.

His most enigmatic wardrobe moment came at the recent derby trouncing match against Manchester United. He refused to explain the meaning behind his "Why always me?" vest that he revealed after scoring. But the fact that he bothered to commission the one-off T-shirt in the first place hints that, in fashion terms, Balotelli has so much more to give.

Imogen Fox

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét